Bad breath (halitosis): a breathtaking topic

Bad breath (also known by the scientific terms ‘halitosis’, ‘oral malodour’ or ‘foetor ex ore’) is a widespread problem. Statistically, around 30% of all people have temporary bad breath and 8% have permanent bad breath. This makes it all the more surprising that such a common phenomenon in our society is a taboo subject. Because they feel ashamed, people affected by this problem do not even talk about it with their closest relatives and spouses and, conversely, are usually not made aware of their bad breath. Also, since you cannot tell that you have bad breath yourself, there is a great deal of uncertainty surrounding how to deal with halitosis. People who are afraid of suffering from bad breath often do not dare to ask someone close to them for advice, further increasing the unspoken fear of social exclusion.

This page is primarily aimed at all patients who are – or are afraid of being – affected by halitosis. A brief summary of all of the key information on the subject of halitosis is provided here according to the latest knowledge.

There is still a widespread misconception that halitosis is mainly caused by stomach problems. It has now been proven that the causes of more than 95% of all cases of halitosis lie in the mouth and throat. So the dentist should always be the first port of call for halitosis patients. As we know that there is a great need for expert advice, we have set up a bad breath consultation in our practice.

Overview of the topic:

The causes of bad breath

‘BAD BREATH’ DUE TO NUTRITION

Everyone knows that, by affecting the air we breathe, a whole range of foods, drinks and tobacco can lead to temporary bad breath, which others around us sometimes find unpleasant. But, in this case, ‘bad breath’ would be a better term than ‘halitosis’, as the cause clearly lies in the air we breathe. The best-known example is garlic. Its aromas are partially excreted when we breathe and can cause halitosis for up to two days after ingestion. Onions, alcohol, cheese, tobacco, smoking, coffee and other food and drink can also have similar effects. This food-related type of bad breath is always harmless and can easily be eliminated by avoiding the food, drinks and tobacco that cause it.

What’s more, prolonged fasting can also promote bad breath due to changes in saliva consistency. It is therefore advisable to eat meals – especially breakfast – regularly.

WHAT DO WE BREATHE OUT?

The air that humans exhale contains around 78% nitrogen, 17% oxygen, 4% carbon dioxide and only around 1% other gases. But this 1% can contain gases that produce a great deal of odour, so despite the low volume share, the odour of the exhaled air is perceived as unpleasant or even unbearable.

The key chemical compounds in this regard are volatile sulphur compounds (e.g. methyl mercaptan, dimethyl sulphide or hydrogen sulphide), but also even smellier substances such as indole, skatole, cadaverine or putrescine. The everyday odour of the air we air exhale is often subject to considerable diurnal fluctuations, which also depend on food intake.

GENUINE BAD BREATH DUE TO BACTERIA

Nowadays, the development of bad breath (halitosis) has been well researched from a scientific standpoint. In almost all cases, bad breath is caused by anaerobic bacteria (that live without oxygen) colonising the mouth or throat and breaking down proteins (protein substances). During the decomposition of these proteins – which may be food residues or dead cells of the body’s own tissue – amino acids are produced first of all. These amino acids are then broken down themselves, releasing foul-smelling gases containing sulphur.

In over 90% of cases, halitosis is caused by:

> Bacteria coating the tongue

> Gingivitis (inflammation of the gums)

> Periodontitis (inflammation of the periodontium)

> Xerostomia (insufficient flow of saliva)

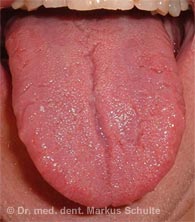

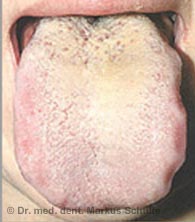

Coatings on the tongue

The tongue has several important functions. It is indispensable for transporting food in the mouth, swallowing, speaking and tasting.

It has now been proven that the back of the tongue is the most common source of bad breath. The furrowed, fissured microstructure (relief) of the tongue and its tastebuds provides excellent living conditions for anaerobic bacteria – i.e. bacteria that live without oxygen (anaerobes) and can colonise a huge surface area here. Around two thirds of all bacteria in the mouth are located on the back of the tongue. The bacteria coating the tongue contains the same germs that are also involved in the development of gingivitis and periodontitis. These microorganisms break down proteins and cause bad breath by producing foul-smelling gases containing sulphur.

Gingivitis

The inflammation of the gums is known as ‘gingivitis’ and affects around 40% of the population. With the exception of rare general medical causes, gingivitis is almost always due to inadequate oral hygiene. Hormonal changes (e.g. during pregnancy) and certain medications can increase the tendency to gum inflammation. The accumulation of bacterial plaque on the teeth leads to the typical signs of gum inflammation: redness, swelling and a tendency to bleed. If the plaque is not removed, gingivitis can develop into periodontitis. Gum problems such as gingivitis or periodontitis often lead to bad breath due to the masses of bacteria present.

Periodontitis

If the bacterial inflammation not only affects the gums, but also attacks the periodontium (e.g. the jawbone supporting the teeth), it is called ‘parodontitis’ – which is popularly known as ‘periodontitis’. Pockets in the gums and bones that pus often drains from form. Pus-filled abscesses sometimes develop too. The extensive colonisation of the pockets with anaerobic bacteria (bacteria that live without oxygen) can lead to severe halitosis in periodontitis patients. Without treatment, widespread periodontitis leads to tooth loss and can also have a negative impact on patients’ general health. You can find detailed information about periodontal diseases and treatment options on our periodontitis and gum problems page.

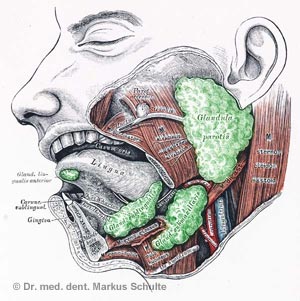

Xerostomia – insufficient flow of saliva

Bad breath caused by bacteria is promoted when the flow of saliva is reduced. Saliva plays an important role in rinsing the mouth and helps to remove food residues from the oral cavity, for example. It can also bind the foul-smelling gases produced during the bacterial decomposition of proteins and also has a certain antibacterial effect.

If too little saliva is produced and the mouth is too dry as a result, this is known as ‘xerostomia’. We now know that insufficient saliva production can be a decisive factor in the development of bad breath.

Interesting information about human saliva

Human saliva contains approximately 99.5% water and 0.5% dissolved components such as mucous substances, proteins and enzymes. Saliva moisturises and protects the mucous membranes and is essential as a lubricant for swallowing solid food. Its protective function against tooth decay is also important. A person produces around 0.5 – 1.5 litres of saliva per day.

Causes of xerostomia may be:

- Taking certain medications that reduce salivation, such as:

- Anticonvulsants

- Medication for depression

- Sedatives and sleeping pills

- Antihistamines for allergies

- Medication that lowers blood pressure

- Diuretics

- Appetite suppressants

- Diseases of the salivary glands

- Condition after radiotherapy in the head area (damage to the salivary glands)

Other potential causes of bad breath

As explained above, over 90% of the source of bad breath is in the oral cavity. So, when examining halitosis patients, an oral cause (located in the mouth) should be sought or ruled out first of all.

In the – admittedly, relatively rare – cases in which halitosis does not originate in the oral cavity, the cause (in descending order of frequency) lies in the following diseases:

> Chronic inflammation of the maxillary sinus or other paranasal sinuses (sinusitis)

> Chronic tonsillitis (inflammation of the palatine tonsils) or tonsil stones

> Chronic rhinitis (inflammation of the mucous membranes in the nose), nasal polyps

> Protrusions of the oesophagus (diverticula) or disruption of the sphincter muscle between the stomach and oesophagus

> In very rare cases, malignant tumours in the mouth, nose, throat or respiratory tract can also be responsible for bad breath

How can bad breath be detected (diagnosed)?

Many people are worried – rightly or wrongly – that they have bad breath (also known as ‘halitosis’). Since it is almost impossible to tell yourself that you have bad breath, and that people often have inhibitions – understandably so – about asking other people they are close to or even strangers for their opinion, it is very important for these patients to receive an objective assessment of their bad breath.

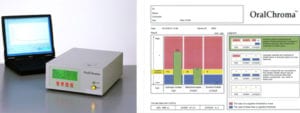

With the bad breath consultation, we are offering our patients the opportunity to determine the presence and, if necessary, the intensity of bad breath without doubt and to investigate what is causing it. We use various proven test procedures in this regard. A detailed questionnaire, which the patient completes before the session (or preferably at home), is helpful. To obtain correct and unbiased examination results, it is important to adhere to certain rules of behaviour the day before attending the bad breath consultation.

You can also book your appointment for the bad breath consultation online. Please download the instructions and the questionnaire beforehand and bring them along with you to your appointment.

Book your appointment online (please select Dr Schulte as the practitioner and ‘Bad breath consultation’ as the treatment).

What are known as ‘organoleptic’ tests are based on how the examiner perceives bad breath using their sense of smell. Standardised methods are used to achieve the most objective assessment possible, and the values determined are carefully documented to enable comparisons with later controls.

The halimeter is an electronic measuring device that enables measurement of the gaseous compounds responsible for halitosis in the patient’s mouth. The OralChroma CHM2 – a latest-generation gas chromatograph – is available in our practice. Using this Japanese-made device, we can separately detect the three main components of bad breath (hydrogen sulphide, methyl mercaptan and dimethyl sulphide) and measure their concentration in the exhaled air.

The application is simple and patient-friendly. Air is sucked out of the patient’s mouth with a syringe and fed into the measuring device. The result is available after just a few minutes. The concentrations of the three key gases responsible for bad breath that are contained in the patient’s breath are displayed separately. This analysis enables us to draw valuable conclusions. Not only can we use the measured values to determine without doubt whether bad breath (halitosis) is present; the distribution of the individual components also provides information on what is causing the halitosis and thus on further treatment.

Even if the halimeter is no replacement for the test methods mentioned previously, it is a valuable tool in objectively assessing halitosis. It also allows progress monitoring, to determine whether the halitosis treatment is having the desired effect. That is why the halimeter has become an indispensable instrument for diagnosing bad breath in our practice.

If the tests and measurements actually confirm the presence of halitosis, the cause of the bad breath must be determined first of all.

As already mentioned, the source of bad breath can be found in the oral cavity in over 90% of cases. So the prospects of permanently eliminating halitosis are very good if this cause can be identified. The entire oral cavity is inspected in detail for this very purpose, with the inspection focusing on the following points in particular:

Examining the back of the tongue

Bacteria coating the tongue are the most common source of halitosis, so particular attention is paid to the tongue. The structure, coatings and discolouration can be used to assess whether bacteria are colonising the tongue. Special test strips that change colour when certain bacteria are present (Halitox) may help with clarifying this matter.

Gum problems

Inflammation of the gums (gingivitis) is caused by bacteria that release sulphurous gases and may cause bad breath. These problems can be identified by carefully inspecting the gums.

Examining the periodontium

If paradontisis (often also referred to as ‘periodontitis’) is present, this leads to bacteria colonising the gum pockets. This also produces gaseous compounds that can be responsible for bad breath. A thorough periodontal examination including measurement of the gum pockets and – if necessary – bacteriological smears and X-rays can detect any periodontitis that may be present.

Examining the teeth

Finally, the teeth are examined for caries, damaged fillings and defective crowns or bridges. Any existing prostheses are also inspected in detail.

Measuring the salivary flow rate

A mouth that is too dry promotes halitosis. So if insufficient saliva production (xerostomia) is suspected, the amount of saliva is measured (in millilitres per minute). Normally, the salivary flow rate stimulated by chewing is between 0.7 and 2.0 ml per minute. If less saliva is produced, the causes must be investigated so that targeted therapy can be recommended. Reduced saliva flow can be caused by diseases of the salivary glands and mental disorders, and can also be an undesirable side effect of taking certain medication. Such medication includes:

> Sedatives

> Anticonvulsants

> Medication for depression

> Antihistamines for allergies

> Medication that lowers blood pressure

> Diuretics

> Appetite suppressants

How can bad breath be treated (what therapy is available)?

TREATING HALITOSIS

In the vast majority of patients suffering from bad breath, halitosis can be effectively treated by treating the intraoral cause (the cause inside the mouth). The treatment depends on the findings obtained during the bad breath consultation.

Cleaning the tongue

As has already been explained, the source of bad breath often lies in bacteria colonising the tongue. This can be remedied by subjecting the tongue to intense mechanical cleaning every day using a suitable tongue cleaner, to which a disinfectant jelly can be applied if necessary. Tongue scrapers and brushes are now available in a wide variety of forms, but not all of them are equally effective. Our dental hygienists will be happy to advise you and instruct you in the technique that is ideal for you.

Treating gingivitis and periodontitis

If the halitosis is caused by bacterial inflammation of the gums (gingivitis) or periodontitis, targeted treatment is urgently required. First of all, the patient must improve their oral hygiene. Periodontal treatment can not only stop bad breath, but also prevent further damage to the gums and periodontium. As periodontology is one of the treatments we focus on, we can draw on the entire range of treatment options available nowadays if necessary – ranging from conservative deep cleaning of the gum pockets, using antibiotics and lasers if necessary, to tissue regeneration. In our periodontology section, you will find detailed information about gum problems, periodontitis and treatment options.

Treating tooth or denture defects

Untreated cavities (tooth decay), defective fillings and poorly fitting crowns, bridges or dentures can sometimes lead to bad breath. In this case, it is advisable to restore the teeth by means of conservative treatment with fillings or inlays or to replace the defective crowns.

Treating dry mouth

If the saliva flow rate is too low, this leads to dry mouth (xerostomia), which can promote the development of halitosis. Since many frequently prescribed medications reduce saliva production, it must first of all be clarified together with the attending medical practitioner whether a lower dosage or switching to other active ingredients may provide relief. In milder forms of xerostomia, the activity of the salivary glands can also be stimulated with the likes of boiled sweets. There are also medications that stimulate saliva production. In severe cases, saliva substitutes can help.

Mouthwashes

Certain mouthwashes have been proven to have a positive effect on bad breath. However, the effect of these mouthwashes is limited and they are not a replacement for actually treating the cause. We recommend such mouthwashes at best as support for treating the actual cause.

Referral to a specialist

If it is not possible to identify an oral cause of the bad breath (in the oral cavity), a thorough examination should be carried out by an ear, nose and throat specialist. The practitioner will inspect the tonsils, nose and paranasal sinuses in particular. If this assessment is also unsuccessful, a gastroenterologist can clarify conclusively whether the halitosis is potentially being caused by a problem in the digestive tract.

How much does the halitosis consultation cost?

The initial examination as part of the halitosis consultation includes a complete examination of the oral cavity and teeth with periodontal findings, as well as organoleptic and halimetric measurement of the oral malodour. This consultation costs approximately CHF 330, plus any necessary X-rays. If a follow-up session with renewed halimetry is necessary, this costs around CHF 145.

You can also book your appointment for the bad breath consultation online. Please download the instructions and the questionnaire beforehand and bring them along with you to your appointment.

Book your appointment online (please select Dr Schulte as the practitioner and ‘Bad breath consultation’ as the treatment)

Would you like to convert CHF (Swiss francs) to EUR (euros)?

Use the online currency converter.

Questions and answers on the topic of bad breath

Yes. It is usually strongest early in the morning after waking up. This is also related to reduced saliva production at night. A good breakfast stimulates the flow of saliva and can significantly reduce halitosis.

Self-tests are difficult and not always reliable. For example, you can blow air into a plastic bag and, after waiting for a short time, smell the air flowing out of the bag. Another option is to rub the back of your tongue vigorously with a cotton bud, then smell it. However, the ‘neutral’ nose of the examining specialist or their electronic measuring device (halimeter) is much more reliable than these methods.

It is, of course, possible that the people you are asking are not telling you the truth. However, there are also people who objectively do not have bad breath, but are firmly convinced that they smell a strong odour from their mouth. This behaviour is known as ‘halitophobia’. Only a professional examination can provide any certainty.

Chewing gum stimulates saliva production and can mechanically reduce coatings on the tongue. So chewing gum is an easy household remedy for halitosis, even if it is only effective for a limited period of time. However, you should be sure to use sugar-free chewing gum to avoid damaging your teeth.

While this is possible in principle, it is very rarely the case (in less than 1% of all cases). If the function of the sphincter muscle between the stomach and oesophagus is impaired (cardia insufficiency) and reflux from the stomach into the oesophagus occurs (reflux), this can sometimes lead to halitosis. But in around 95% of cases, the cause of halitosis lies in the mouth, and in 4% in the tonsils, nose or maxillary sinuses.

Yes. Many commonly prescribed medications cause a reduction in saliva production in the mouth and thus promote the development of halitosis.

Yes. Bad breath is much more common in older people than in younger people. This is also related to the decrease in saliva production as we age. In addition, older people have periodontitis more often than younger people.

Yes. Even if the connections are not yet clear, it has been proven that psychological stress can promote bad breath.

Certain sulphurous compounds that produce a great deal of odour and that are contained in smoke enter the bloodstream via the lungs when people are smoking, and they are then released again via the lungs, resulting in smokers having the typical ‘smoker’s breath’. However, heavy smokers also often have a reduced flow of saliva, promoting the development of ‘genuine’ halitosis.

A removable dental prosthesis can sometimes promote the build-up of bacteria or bacterial plaque and lead to parts of the oral mucosa drying out. So perfect denture hygiene is crucial to prevent halitosis.